What To Do When Someone I know becomes Disabled Part 3

DISABILITY LAW – What To Do When a Client or Someone I know becomes Disabled – Part 3

Author Attorney Greg Reed:

Updated: 1/31/2023

This is Part 3 of a speech presented by Bemis, Roach & Reed partner Greg Reed at the

CAPITAL AREA PARALEGAL ASSOCIATION in Austin Texas, April 27, 2016

This Document can be downloaded in it’s entirety in PDF format here

<- Back to Part 1

<- Back to Part 2

Greg Reed is a partner in the Austin law firm of Bemis, Roach & Reed. He received his law degree in 1991 from the University of Texas at Austin. He is Board Certified in Personal Injury Trial Law by the Texas Board of Legal Specialization and AV rated by Martindale-Hubbell. He has been SuperLawyers® Rated by Thomson Reuters. Mr. Reed is admitted to every federal district in Texas and is a recognized authority in representing claimants with Long Term Disability and Social Security Disability claims.

Acknowledgement

My law partner, Lonnie Roach, researched and wrote the section of this paper related to ERISA disability. Lonnie Roach is a partner in the Austin law firm of Bemis, Roach & Reed. He received his law degree in 1991 from the University of Texas at Austin. He is Board Certified in Personal Injury Trial Law by the Texas Board of Legal Specialization and AV rated by Martindale-Hubbell. He has been SuperLawyers® Rated by Thomson Reuters. Mr. Roach is admitted to every federal district in Texas and focuses his practice on representing claimants with ERISA Long Term Disability claims.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Part 1

PUBLIC DISABILITY BENEFITS –SSDI AND SSI

- Definition of Disability

- Disability Determination

- Appeal Process

Part 2

PRIVATE DISABILITY – CLAIMS AGAINST DISABILITY INSURERS

- What is an ERISA plan?

- Should be in writing.

- What minimum indicia can define a plan – insurance policy, criterion/critical factors?

- Some plans fall within the Safe Harbor provision.

- What is not an ERISA plan?

- Who are the plan principals?

- Who are fiduciaries?

- What is the obligation of a fiduciary?

Part 3

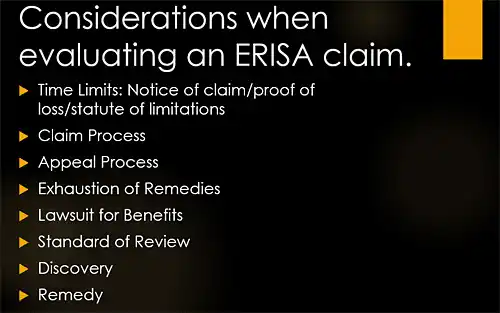

CONSIDERATIONS WHEN EVALUATING AN ERISA CLAIM:

- Time Limits: Notice of Claim/Proof of Loss/Statute of Limitations

- Claim Process

- Appeal Process

- Exhaustion of Remedies

- Lawsuit For Benefits

- Standard of Review

- Discovery

- Remedy

CONCLUSION

DISABILITY LAW OVERVIEW

Americans are filing for disability benefits at a startling rate. Since 2003, there has been a 44% increase in disability claims filed by people previously in the workplace. Claims for disability by individuals with little or no work experience increased by 29% over the same time. The conjecture is that a combination of an aging population and a slowing economy caused the growth in disability claims.

Public or Private

Disability benefits come from many different sources and the rules for obtaining benefits change based on the source of the benefit. This paper will discuss the most common public disability benefits, Social Security Disability Insurance and Supplemental Security Income, and will also discuss the most common private disability insurance. It does not address veteran’s disability benefits or federal employee disability benefits.

A. Time Limits: Notice of Claim/Proof of Loss/Statute of Limitations

1. Notice of Claim/Proof of Loss

Most benefits plans have requirements regarding the timing of both the claimant’s notice of claim and the more formal proof of loss. These requirements are found within the terms of the plan which may be either in the summary plan description (SPD) or the insurance policy if such exists. The notice of claim is generally described as the initial notice to the administrator or the insurance carrier that a participant is claiming, or is intending to claim, certain benefits under the Plan. In contrast, the proof of loss is the statement of facts, usually along with supporting documentation that proves facts supporting the claim and the triggering of benefits afforded by the Plan.

Both the notice of claim and proof of loss are generally required to be submitted by the participant to the proper administrator or fiduciary within certain prescribed periods of time. The notice of claim is often within thirty (30) days of the event triggering the initiation of a claim. Proof of loss generally required to be given no later than one year after the notice of claim or benefit-triggering event.

Sometimes the claimant does not or cannot give either timely notice or timely proof of loss or both. What is the effect of a claimant’s failure to give timely notice of claim or proof of claim? In Texas and most other state jurisdictions, the notice-prejudice rule has been adopted for insured claims. PAJ, Inc. v. Hanover Insurance Co., 243 S.W.3d 630, 634 (Tex. 2008). This rule requires that the administrator first prove that it has suffered actual prejudice as a result of the late notice or filing in order to raise a claim forfeiture defense. Although a state law, the doctrine is not preempted under ERISA due to its direct regulatory effect on the business of insurance. UNUM Life Insurance Co. v. Ward, 119 S.Ct. 1380, 1386-1387 (1999).

2. Statute of Limitations

a. Claim for benefits – 4 years. ERISA contains no distinct statute of limitations for claims for benefits brought under § 502(a)(1). For these cases, the circuits agree that the state-law statutes of limitations for breach of contract should be applied. See e.g. Hogan v. Kraft Foods, 969 F.2d 142, 145 (5th Cir. 1992). In Texas, the 4 year period found in Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code § 16.004 is used unless the Plan establishes a different period.

b. Interference with ERISA rights – 2 years. Claims brought under § 510 of ERISA, typically for retaliation for exercising ERISA rights, are viewed by the Fifth Circuit as most analogous to state-law tort claims and therefore do not use the same statute of limitations as do claims for benefits. In Texas, the two year period, found in Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code § 16.003, is applied. McClure v. Zoecon, Inc., 936 F.2d 777 (5th Cir. 1991).

c. Breach of Fiduciary Duty – 3 years (could be as long as 6 years by ERISA statute § 413).

Individualized claims for breach of fiduciary duty were recognized by the U.S. Supreme Court in Varity v. Howe, 516 U.S. 489, 116 S.Ct. 1065, 134 L.Ed.2d 130 (1996). These claims, brought under § 502(a)(3) are subject to the only statute of limitations actually found in ERISA. Section 413 provides:

No action may be commenced under this subchapter with respect to a fiduciary’s breach of any responsibility, duty, or obligation under this part, or with respect to a violation of this part, after the earlier of: (1) six years after (A) the date of the last action which constituted a part of the breach or violation, or (B) in the case of an omission the latest date on which the fiduciary could have cured the breach or violation, or (2) three years after the earliest date on which the plaintiff had actual knowledge of the breach or violation; except that in the case of fraud or concealment, such action may be commenced not later than six years after the date of discovery of such breach or violation.

The Fifth Circuit has held that § 413 is actually a statute of repose which establishes “an outside limit of six years in which to file suit, and tolling does not apply” Radford v. General Dynamics Corp., 151 F.3d 396, 400 (5th Cir. 1998). This appears to be true even though Fifth Circuit precedent may require a claimant to exhaust administrative remedies before filing a breach of fiduciary duty claim. See, Simmons v. Willcox, 911 F.2d 1077 (5th Cir. 1990).

3. Exceptions to general rule.

a. Different time limitation in the Plan

Many (if not most) plans contractually modify the period for limitations by inserting a different period of time in which to bring a cause of action. These contractual modifications of a claimant’s statute of limitations are enforced so long as they are found to be reasonable. Harris Methodist Forth Worth v. Sales Support Servs. Inc. Employee Health Care Plan, 426 F.3d 330 (5th Cir. 2005). Reasonableness, however, is in the eye of the beholder. The Fifth Circuit has found a limitations period of 120 days to be reasonable in the context of a disability benefit claim under § 502(a)(1). See, Dye v. Associates First Capital Corp. Long-Term Disability Plan 504, 243 Fed.Appx. 808 (5th Cir. 2007) (Not pub.). Moreover, in Dye, the court acknowledged decisions from other circuits finding limitations periods as short as 45 days to be reasonable and gives no indication that this time frame would be found unreasonable in the Fifth Circuit.

Although the Fifth Circuit ostensibly looks to state-law for guidance in limitations cases, it refused to do so with respect to an important safety net Texas provides. Texas Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code 16.070(a) provides:

“…a person may not enter a stipulation, contract, or agreement that purports to limit the time in which to bring suit on the stipulation, contract, or agreement to a period shorter than two years. A stipulation, contract or agreement that establishes a limitations period that is shorter than two years is void in this state. ”

Despite the clear policy evidenced by this statute, the Court in Dye summarily dismissed an argument that it provided an analogous state period of limitations citing only a Texas court of appeals case that held § 16.070(a) is not binding on ERISA claims. See, Hand v. Stevens Trans. Inc. Employee Benefit Plan, 83 S.w.3d 286 (Tex.App. Dallas 2002).

b. Limitations tolled during administrative appeal?

In light of the requirement that a claimant exhaust administrative remedies before filing suit, it would seem to follow that limitations are tolled while those administrative remedies are pursued. This is not necessarily true, however. As stated above, the Fifth Circuit in Radford expressly rejected the notion that limitations are tolled while mandatory administrative appeals are pursued in breach of fiduciary duty claims. The Fifth Circuit has yet to expressly decide whether pursuit of administrative remedies tolls limitations for claims for benefits cases.

At least one District court has, however. In Buckley v. Hartford Life and Accident Ins. Co., 2007 WL 2701397, the District court examined this issue and

found that it would be unfair to allow limitations to run while simultaneously requiring a claimant to exhaust administrative remedies.

B. Claim Process

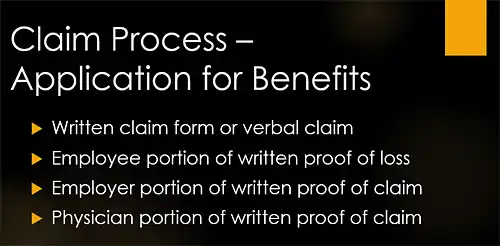

1. Application for Benefits

a. written claim form or verbal claim – sometimes referred to as a Aproof of loss.@

b. employee portion of written proof of loss – biographical information, reason for disability or other loss, restrictions and limitations, etc.

c. employer portion of written proof of claim – biographical information, job description, monthly pay and miscellaneous questions.

d. physician portion of written proof of claim – period of treatment, restrictions and limitations, perhaps diagnosis (postage stamp space for answers), and treatment records.

2. Deadlines

a. Deadlines in the Plan

Most ERISA plans incorporate the deadlines for claims procedure found in the regulations published by the U.S. Department of Labor. These deadlines can however change from time to time and there is often considerable lag time before a particular plan is updated. Some claimants who have been receiving benefits for a long period of time, such as in long term disability cases, may be operating under plan terms that are substantially different than those found in the federal code. The careful practitioner will review each plan for deadlines and compare with the federal regulations so that any departures from the current regulations are noted. It is not safe to assume that a plan deadline that differs from the appropriate deadline in the regulations is void. The Fifth Circuit has held that technical noncompliance with ERISA procedures will be excused so long as the claimant is not denied a full and fair review. Robinson v. Aetna, 443 F.3d 389, 393 (5th Cir. 2006).

b. Deadlines in the federal code

The Code of Federal Regulations, at 29 C.F.R. 2560.503-1, lists the chronological deadlines each plan is required to adopt if it is to be determined to provide a Afull and fair@ review of denied claims as required by ERISA ‘ 503. The deadlines vary depending on the nature of the claim.

(1) Health claims (non urgent)

90 days from receipt of claim Plan must notify claimant of initial adverse benefit determination. May be extended up to an additional 90 days should circumstances require.

180 days from receipt of adverse benefit determination:

Claimant must appeal adverse benefit determination.

60 days from receipt of appeal (Post service claims only)

Plan must notify claimant of decision on appeal.

(2) Disability claims

45 days from receipt of claim Plan must notify claimant of initial adverse benefit determination. May be extended up to an additional 60 days should circumstances require.

180 days from receipt of adverse benefit determination:

Claimant must appeal adverse benefit determination.

45 days from receipt of appeal Plan must notify claimant of decision on appeal. May be extended an additional 45 days if circumstances require.

(3) Other claims

90 days from receipt of claim Plan must notify claimant of initial adverse benefit determination. May be extended up to an additional 90 days should circumstances require.

60 days from receipt of adverse benefit determination:

Claimant must appeal adverse benefit determination.

60 days from receipt of appeal Plan must notify claimant of decision on appeal. May be extended an additional 60 days if circumstances require.

3. Obtaining Documents By Which The Plan Is Operated

ERISA plans are typically governed by a written document. In most situations, the employee would be provided with a summary plan description (SPD), a much shorter and easier to read document, in lieu of the formal plan document. If an employee needs to make a claim under the employee benefit plan, that employee would most likely start with the SPD. The plan and summary plan description provide the employee with the description of the benefits of the plan and how to make a claim.

The SPD, or for that matter the plan document may instead refer to a particular insurance policy which sets out the benefits and/or the claim procedure. If the employee does not have the SPD or insurance policy, he/she may request it. Similarly, the employee may request a copy of relevant documents pertaining to the denial of the claim. The plan is required to produce relevant documents upon receipt of a proper, written request.

Request relevant documents – definition of relevant, 29 C.F.R. ‘ 2560.503-1(m)(8), from the plan:

- relied on in making benefit determination;

- submitted, considered or generated in the course of making benefit determination, regardless of whether relied on;

- demonstrates compliance with administrative procedures in making benefit determination in accordance with plan documents; and

- in case of group health or disability benefits, constitutes a statement of policy with concerning the denied treatment, regardless of whether relied on in making benefit determination. 29 C.F.R. ‘ 2650.503-1(m).

Upon receipt of a proper request, a plan is required to provide requested documents within 30 days. Failure of the plan to do so is actionable under 29 U.S.C. ‘ 1132(c). ERISA provides for a penalty of up to $110.00 per day for failure to provide documents in response to a request.

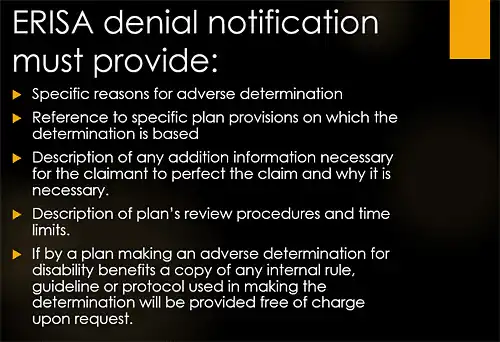

4. Denial Letter

The denial letter must provide the information required by ERISA (29 U.S.C. ‘ 1133) and ERISA regulations (29 C.F.R. ‘ 2560.503-1(f)) Weaver v. Phoenix Home Life Mut. Ins. Co., 990 F.2d 154 (4th Cir. 1993) (Non-compliance with ‘1133(1) was evidence of abuse of discretion but did not require a heightened standard of review.)

ERISA regulations list the requirements of a proper, adverse benefit determination:

(g) Manner and content of notification of benefit determination.

(1) Except as provided in paragraph (g)(2) of this section, the plan administrator shall provide a claimant with written or electronic notification of any adverse benefit determination. . . . The notification shall set forth, in a manner calculated to be understood by the claimant B

(i) The specific reason or reasons for the adverse determination;

(ii) Reference to the specific plan provisions on which the determination is based;

(iii) A description of any additional material or information necessary for the claimant to perfect the claim and an explanation of why such material or information is necessary;

(iv) A description of the plan’s review procedures and the time limits applicable to such procedures, including a statement of the claimant’s right to bring a civil action under section 502(a) of the Act following an adverse benefit determination on review;

(v) In the case of an adverse benefit determination by a group health plan or a plan providing disability benefits, (A) If an internal rule, guideline, protocol, or other similar criterion was relied upon in making the adverse determination, either the specific rule, guideline, protocol, or other with the specific rule, guideline, protocol, or other similar criterion; or a statement that such a rule, guideline, protocol, or other similar criterion was relied upon in making the adverse determination and that a copy of such rule, guideline, protocol, or other similar criterion will be provided free of charge upon request. . . .

29 C.F.R. ‘ 2560.503-1 (g).

5. Administrative Record

The administrative record consists of the documents available, reviewed or relied on by the administrator of the plan to evaluate a particular claim. It necessarily includes the plan document governing the claim (usually the Summary Plan Description or insurance policy) and the entire claim file that was compiled during the claim and appeal process. It is the responsibility of the plan administrator to identify the matters to include in the administrative record and the claimant can thereafter object to the completeness of the record. See e.g. Barhan v. Ry-Ron Inc. 121 F. 3d 198, 201-202 (5th Cir. 1997). Once the administrative record is complete, a district court reviewing a decision of the administrator is constrained to the factual evidence before the administrator. Robinson v. Aetna, 443 F. 3d 389, 394 (5th Cir. 2006).

C. Appeal Process

ERISA, ‘ 503 provides:

Sec. 1133. Claims procedure

In accordance with regulations of the Secretary, every employee benefit plan shall–

1. provide adequate notice in writing to any participant or beneficiary whose claim for benefits under the plan has been denied, setting forth the specific reasons for such denial, written in a manner calculated to be understood by the participant, and

2. afford a reasonable opportunity to any participant whose claim for benefits has been denied for a full and fair review by the appropriate named fiduciary of the decision denying the claim.

A claimant who receives an adverse benefit determination must be afforded an opportunity for a Afull and fair@ review. This review, directed to the appropriate fiduciary, is the administrative appeal. It can be made with or without supporting documentation. Since the ERISA administrator is required to give its specific reasons for the denial of the claim, the administrative appeal need only be directed at those specific reasons, not the termination of benefits generally. Robinson v. Aetna Life Ins. Co., 443 F.3d 389, 393 (5th Cir. 2006). This means the administrator must state all the grounds on which it ultimately relies in the original denial letter. Id. Citing McCartha v. Nat’s City Corp., 419 F.3d 437, 446 (6th Cir. 2005). The requirement that the administrator disclose the basis for its decision is necessary so that the beneficiary can adequately prepare for any further administrative review. Schadler v. Anthem Life Ins., 147 F.3d 388, 394 (5th Cir. 1998).

The most obvious reason for filing an administrative appeal is the hope that the plan administrator will reconsider the adverse benefit determination and award or restore benefits. Pursuing all required administrative appeals is also a necessary prerequisite for filing suit. Although a plan may allow for unlimited administrative appeals, it may require no more than two for health and disability claims. 29 C.F.R. 2560.503-1(c)(2).

The administrative appeal, along with any supporting documentation, becomes part of the administrative record. At the conclusion of the appeal process, the administrative record closes. Once the administrative record is determined, the Court is precluded from receiving evidence to resolve disputed material facts. Vega v. National Life Ins. Services Co., 188 F.3d 287, 299 (5th Cir. 1999 (en banc)). For this reason, it is imperative that all necessary evidence a party requires to successfully litigate a case be included in the record at the time of appeal or submitted along with the appeal.

D. Exhaustion of Remedies

ERISA contains no specific requirement that a claimant exhaust administrative remedies before filing suit in benefits cases in federal court. Virtually every circuit, however requires this. See e.g. Lacy v. Fulbright & Jaworski, 405 F.3d 254 (5th Cir. 2005). As a general rule, a claimant should always exhaust administrative remedies prior to filing suit. As a judicially created doctrine, however, the district court does have discretion to waive the requirement that a claimant exhaust administrative remedies if the claimant can show exhaustion of administrative remedies would be futile. Denton v. First Nat’l Bank of Waco, Tex., 765 F.2d 1295 (5th Cir. 1985).

Should a claimant file suit before exhausting administrative remedies, the suit is subject to dismissal, typically without prejudice. See e.g. Galvan v. SBC Pension Benefit Plan, 204 Fed.Appx. 335 (5th Cir. 2006).

In breach of fiduciary duty cases, there is conflicting Fifth Circuit precedent on whether exhaustion of administrative remedies is required. Compare, Simmons v. Willcox, 911 F.2d 1077 (5th Cir. 1990) and Galvan, supra. The distinction appears to rest on whether the breach of fiduciary duty claim is predicated on a claim for benefits. If so, then a claimant must exhaust administrative remedies. If not, then exhaustion is not required.

E. Lawsuit For Benefits

1. Claim for Benefits

Plaintiff has a claim against the plan for the recovery of plan benefits owed and is brought pursuant to the ERISA civil enforcement provision which provides “A civil action may be brought . . . (1) by a participant or by a beneficiary . . . (B) to recover benefits due to him under the terms of his plan, to enforce his rights under the terms of the plan, or to clarify his rights to future benefits under the terms of the plan.” 29 U.S.C. ‘ 1132(a)(1)(B).

2. Civil Interference with rights to receive benefits.

It shall be unlawful for any person to discharge, fine, suspend, expel, discipline, or discriminate against a participant or beneficiary for exercising any right to which he is entitled under the provisions of an employee benefit plan, this subchapter, section 1201 of this title, or the Welfare and Pension Plans Disclosure Act (29 U.S.C. §301 et seq.), or for the purpose of interfering with the attainment of any right to which such participant may become entitled under the plan, this subchapter, or the Welfare and Pension Plans Disclosure Act. It shall be unlawful for any person to discharge, fine,

suspend, expel, or discriminate against any person because he has given information or has testified or is about to testify in any inquiry or proceeding relating to this chapter or the Welfare and Pension Plans Disclosure Act. The provisions of section 1132 of this title shall be applicable in the enforcement of this section. 29 U.S.C. ‘ 1140.

3. Jurisdiction/Venue

With rare exception, ERISA cases are litigated in federal court. ERISA contains a specific jurisdictional provision at 29 U.S.C. ‘ 1132(e) granting exclusive jurisdiction of breach of fiduciary duty claims (29 U.S.C. ‘ 1109) and interference with the right to receive benefits claims (29 U.S.C. ‘ 1140) to federal district court. ERISA grants concurrent jurisdiction of claim for benefits cases (29 U.S.C. ‘ 1132(a)(1)(B)) to federal district court and AState courts of competent jurisdiction.@ These cases are typically removed to federal court, however if filed in state court.

ERISA provides a choice of venue for cases filed in federal court allowing them to be brought: Ain the district where the plan is administered, where the breach took place, or where a defendant resides or may be found, and process may be served in any other district where a defendant resides or may be found.@ 29 U.S.C. ‘ 1132(e).

4. Preemption

In order to provide a uniform system of regulating employee benefits, ERISA preempts most state laws and regulations that would otherwise govern employer provided benefits. While this increases efficiency for multi-state employers and ERISA plans by not subjecting them to differing states= regulations for the same plans, it unfortunately leaves little in the way of regulation for most of these plans. ERISA was never intended to provide the regulatory framework for day to day issues such as administering a claimant=s health insurance claim; that job was traditionally done by the states. In the years since its adoption however, most courts have ruled that state regulations, such as the Texas Insurance Code and states= common law simply do not apply to ERISA plans.

Most state laws which “relate to” employee benefit plans are preempted by ERISA. Pilot Life Ins. Co. v. Dedeaux, 481 U.S. 41 (1987) (concerning a broadly-based Mississippi bad faith rule.) The conventional analysis is that ERISA provides, with certain narrow exceptions, that the rights, regulations, and remedies afforded by that statute “supersede any and all State laws insofar as they may now or hereafter relate to any employee benefit plan.” 29 U.S.C. ‘ 1144(a). For purposes of preemption, “[t]he term ‘State law’ includes all laws, decisions, rules, regulations, or other State action having effect of law, of any State.” 29 U.S.C. ‘ 1144(c)(1).

ERISA contains two clauses dealing with the scope of preemption. The preemption clause and the savings clause. The preemption clause provides that, Aexcept as provided in [the savings clause] the provisions of this title . . . shall supersede any and all State laws insofar as they may or now or hereafter relate to any employee benefit plan.” ERISA ‘ 514(a) codified at 29 U.S.C. ‘ 1144(a). The savings clause provides that “. . . nothing in this title shall be construed to exempt or relieve any person from any law of any State which regulates insurance . . . .“ ERISA ‘ 514(b)(2)(A) codified at 29 U.S.C. ‘ 1144(b)(2)(A).

F. Standard of Review

ERISA provides federal courts with jurisdiction to review benefit determinations. See 29 U.S.C. ‘ 1132(a)(1)(B); Baker v. Metro. Life Ins. Co., 364 F.3d 624, 629 (5th Cir. 2004). An administrator=s denial of benefits under an ERISA plan is reviewed by the district court under a de novo standard unless the benefit plan gives the administrator discretionary authority to determine eligibility for benefits or to

construe the terms of the plan. Firestone Tire and Rubber Co. v. Bruch 489 U.S. 101, 115, 109 S. Ct. 948, 103 L. Ed. 2d 80 (1989). When the plan fiduciary is vested with the discretionary authority to determine disability claims under the plan, a district court may reverse the decision regarding a denial of benefits if the decision is arbitrary and capricious. Robinson v. Aetna Life Ins. Co., 443 F.3d 389, 395 (5th Cir. 2006). A decision is arbitrary and capricious if made without a rational connection between the known facts and the decision, or between the found facts and the evidence. Bellaire Gen. Hosp. V. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Mich., 97 F.3d 822, 828 (5th Cir. 1996). An administrator’s decision to deny benefits must be “based on evidence, even if disputable, that clearly supports the basis for its denial.” Vega v. Nat=l Life Ins. Servs., Inc., 188 F. 3d 287, 299. Without some concrete evidence in the administrative record that supports the denial of the claim, the Court must find the administrator abused its discretion. Id. An administrator cannot unreasonably rely on statements contained in the record without considering them in the context of all the relevant facts and evidence presented. See e.g. Lain v. UNUM Life Insurance Company of America 279, F. 3d 337, 346 (5th Cir. 2002).

Upon electing to deny a claim, administrators are required by ERISA, 29 U.S.C. ‘ 1133 to:

1. provide adequate notice in writing to any participant or beneficiary whose claim for benefits under the plan has been denied, setting forth the specific reasons for such denial, written in a manner calculated to be understood by the participant, and

2. afford a reasonable opportunity to any participant whose claim for benefits has been denied for a full and fair review by the appropriate named fiduciary of the decision denying the claim.

Subsection (1)=s mandate that the claimant be specifically notified of the reasons for an administrator=s decision suggests that it is those Aspecific reasons@ rather than the termination of benefits generally that must be reviewed under subsection (2). Robinson, 443 F.3d at 393.

The standard of review for an administrator’s actions is de novo or abuse of discretion based on the determination of whether the administrator has the discretion to determine eligibility for benefits or to construe the terms of the plan. If the administrator does not have this discretion, the district court should apply the de novo standard of review for the law aspects of the decision by the administrator. However, in the Fifth Circuit the factual aspects of the decision by the administrator are nevertheless, always reviewed for abuse of discretion. Estate of Bratton v. Nat.’l Union Fire Ins. Co. of Pittsburgh, Pa., 215 F. 3d. 516, 522 (5th Cir. 2000). Firestone Tire & Rubber Co. v. Bruch, 489 U.S. 101, 115, 109 S.Ct. 948, 946, 103 L. Ed. 2d 80 (1989).

On the other hand, if the plan administrator is determined to have discretionary authority to determine eligibility for benefits or to construe the terms of the plan, in the Fifth Circuit, the review of both the administrators’ law and factual aspects of the decision is based on abuse of discretion.

Oftentimes, an ERISA administrator both determines eligibility benefits and pays benefits out of its own pocket. This is typical with fully insured ERISA plans. In this circumstance, the ERISA administrator operates under a conflict of interest. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co. v. Glenn, 128 S.Ct. 2343, 2348, 76 USLW 4495, 171 L.Ed.2d 299 (2008). This conflict must be weighed as a factor in determining whether there is an abuse of discretion. Id. The fact that an ERISA administrator reached its decision to deny while burdened by a conflict of interest can serve as a tiebreaker should the Court find other factors are closely balanced. Glenn, at 2351.

A reviewing court may give more weight to a conflict of interest, where the circumstances surrounding the plan administrator’s decision suggest “procedural

unreasonableness.” Schexnayder v. Hartford Life & Accident Ins. Co., 600 F.3d 465, 469 (5th Cir. 2010). A decision demonstrates procedural unreasonableness where, for example, an administrator takes positions that are financially advantageous by emphasizing evidence which supports denial of benefits and deemphasizing other evidence. Glenn, 554 U.S. 118, 128 S.Ct. at 2352.

In Glenn, Court held:

Often the entity that administers the plan, such as an employer or an insurance company, both determines whether an employee is eligible for benefits and pays benefits out of its own pocket. We here decide [1] that this dual role creates a conflict of interest; [2] that a reviewing court should consider that conflict as a factor in determining whether the plan administrator has abused its discretion in denying benefits; and [3] that the significance of the factor will depend upon the circumstances of the particular case.

In so holding, the Court reconfirmed several of the principles in Firestone Tire and Rubber Co. v. Bruch, 489 U.S. 101, 109 S.Ct. 948, (1989) where it stated:

(1) In “determining the appropriate standard of review,” a court should be “guided by principles of trust law”; in doing so, it should analogize a plan administrator to the trustee of a common-law trust; and it should consider a benefit determination to be a fiduciary act (i.e., an act in which the administrator owes a special duty of loyalty to the plan beneficiaries). [*11] Id., at 111-113, 109 S. Ct. 948, 103 L. Ed. 2d 80. See also Aetna Health Inc. v. Davila, 542 U.S. 200, 218, 124 S. Ct. 2488, 159 L. Ed. 2d 312 (2004); Central States, Southeast & Southwest Areas Pension Fund v. Central Transport, Inc., 472 U.S. 559, 570, 105 S. Ct. 2833, 86 L. Ed. 2d 447 (1985).

. . .

(4) If “a benefit plan gives discretion to an administrator or fiduciary who is operating under a conflict of interest, that conflict must be weighed as a ‘factor in determining whether there is an abuse of discretion.'” Firestone, supra, at 115, 109 S. Ct. 948, 103 L. Ed. 2d 80 (quoting Restatement ‘ 187, Comment d; emphasis added; alteration omitted).

The Court stated that the payor/determiner conflict is one of the types of conflicts that must be taken into account by the reviewing court. The Court stated:

The employer’s fiduciary interest may counsel in favor of granting a borderline claim while its immediate financial interest counsels to the contrary. Thus, the employer has an “interest . . . conflicting with that of the beneficiaries,” the type of conflict that judges must take into account when they review the discretionary acts of a trustee of a common-law trust. . . . cf. Black’s Law Dictionary 319 (8th ed. 2004) (“conflict of interest” is a “real or seeming incompatibility between one’s private interests and one’s public or fiduciary duties”).

Id. at *12-*13.

The Court reasoned that the dual role of payor/determiner created a conflict because:

… ERISA imposes higher-than-marketplace quality standards on insurers. It sets forth a special standard of care upon a plan administrator, namely, that the administrator “discharge [its] duties” in respect to discretionary claims processing “solely in the interests of the participants and beneficiaries” of

the plan, ‘ 1104(a)(1); it simultaneously underscores the particular importance of accurate claims processing by insisting that administrators “provide a ‘full and fair review’ of claim denials,” Firestone, 489 U.S., at 113, 109 S. Ct. 948, 103 L. Ed. 2d 80 (quoting ‘ 1133(2)); and it supplements marketplace and regulatory controls with judicial review of individual claim denials, see ‘ 1132(a)(1)(B).

Id. at, *17 (emphasis supplied).

The Court reiterates that the conflict must be taken into account. ATrust law continues to apply a deferential standard of review to the discretionary decision making of a conflicted trustee, while at the same time requiring the reviewing judge to take account of the conflict when determining whether the trustee, substantively or procedurally, has abused his discretion.@ Id. at *18 (emphasis supplied). The reviewing judge must determine the lawfulness of the benefits denial by taking into account several factors, including conflict, reaching a result by weighing all together. The Court has fashioned a facts-and-circumstances reasonableness test to administrative decisions.

The reviewing court must also determine the inherent or case-specific importance of the conflict factor based on the likelihood that it affected the claim decision. The Court stated, “The conflict of interest at issue here, for example, should prove more important (perhaps of great importance) where circumstances suggest a higher likelihood that it affected the benefits decision. . .” Id. at *21. The Court also noted that certain conduct by the administrator may give weight to the conflict. “This course of events was not only an important factor in its own right (because it suggested procedural unreasonableness), but also would have justified the court in giving more weight to the conflict (because MetLife’s seemingly inconsistent positions were both financially advantageous).” Id. at *23.

Where, at the opposite end, the factor may be less important based on precautions taken by the administrator. “It should prove less important (perhaps to the vanishing point) where the administrator has taken active steps to reduce potential bias and to promote accuracy, for example, by walling off claims administrators from those interested in firm finances, or by imposing management checks that penalize inaccurate decision making irrespective of whom the inaccuracy benefits.” Id. at *21-*22.

The Supreme Court approved of the Sixth Court of Appeals= weighing of the factors in performing the combination-of-factors method of review. The Court stated:

The Court of Appeals’ opinion in the present case illustrates the combination-of-factors method of review. The record says little about MetLife’s efforts to assure accurate claims assessment. The Court of Appeals gave the conflict weight to some degree; its opinion suggests that, in context, the court would not have found the conflict alone determinative. See 461 F.3d at 666, 674. The court instead focused more heavily on other factors. In particular, the court found questionable the fact that MetLife had encouraged Glenn to argue to the Social Security Administration that she could do no work, received the bulk of the benefits of her success in doing so (the remainder going to the lawyers it recommended), and then ignored the agency’s finding in concluding that Glenn could in fact do sedentary work. See id., at 666-669. This course of events was not only an important factor in its own right (because it suggested procedural unreasonableness), but also would have justified the court in giving more weight to the conflict (because MetLife’s seemingly inconsistent positions were

both financially advantageous). And the court furthermore observed that MetLife had emphasized a certain medical report that favored a denial of benefits, had de-emphasized certain other reports that suggested a contrary conclusion, and had failed to provide its independent vocational and medical experts with all of the relevant evidence. See id., at 669-674. All these serious concerns, taken together with some degree of conflicting interests on MetLife’s part, led the court to set aside MetLife’s discretionary decision. See id., at 674-675. We can find nothing improper in the way in which the court conducted its review.

Id. at *22-*24.

G. Discovery

Except for the production and determination of the administrative record, there is no discovery on the fact resolution of the plan=s/insurance company=s decision. On some issues however, discovery is allowable.

In Glenn, the Court’s opinion appears to make it clear that discovery is appropriate and proper regarding the existence of various areas of conflict. It is even clearer that discovery is necessary to show the “case-specific” importance of the conflict as a factor. The Court stated “The conflict of interest at issue here, for example, should prove more important (perhaps of great importance) where circumstances suggest a higher likelihood that it affected the benefits decision,. . .” Metropolitan Life Ins. Co. at *21. Discovery is appropriate to show that the areas of conflict affected the decision.

The Court envisioned that a claimant would have discovery with respect to the payor/determiner conflict as well as conflicts of that type and whether those conflicts affected the benefit determination. Without such discovery, it would be difficult for a claimant to convince a court that a conflict existed or to demonstrate the importance of that conflict as a factor, if the claimant is not given an opportunity for discovery regarding those issues.

Prior to its adoption of the combination of factors review standard post Glenn, the Fifth Circuit recognized that discovery is appropriate in matters related to the degree of deference that should be accorded to an administrator’s decision: “[T]he arbitrary and capricious standard may be a range, not a point. There may be in effect a sliding scale of judicial review of trustees’ decisions-more penetrating the greater is the suspicion of partiality, less penetrating the smaller that suspicion is ….” Vega v. Nat’l Life Ins. Services, Inc., 188 F.3d 287, 296 (5th Cir. 1999) en banc, citing Wildbur v. ARCO Chemical Co., 974 F.2d 631, 638 (5th Cir. 1992); This is based on the Court=s statement that “[t]he greater the evidence of conflict on the part of the administrator, the less deferential our abuse of discretion standard will be.” Lain v. UNUM Life Ins. Co. of America, 279 F.3d at 343, citing Vega v. Nat’l Life Ins. Services, Inc., 188 F.3d at 297. Wildbur v. ARCO Chemical Co.,974 F.2d 631, 638 (5th Cir. 1992), states “[It is] obvious that some evidence other than that contained in the administrative record may be relevant at both steps of this process of judicial review.”

While the sliding scale standard of review is no longer used in the Fifth Circuit, there is no reason why the same type of discovery related to the extent of a conflict of interest would not be allowed in support of the combination of factors approach.

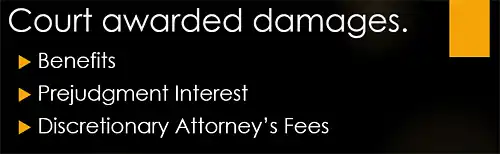

H. Remedy

Upon finding that an ERISA administrator abused it’s discretion, the Court should award damages, including prejudgment interest and attorney fees. Vega v. Natl. Life Ins. Services Inc., 188 F.3d 287,302 & n. 13 (5th Cir. 1999).

1. Benefits

Damages include benefits wrongfully withheld as a result of the denial. In addition to past monetary benefits, such as in the case of life or disability insurance, benefits can include precertification of health benefits or an order that certain benefits be provided (clarification of the right to receive future benefits, §502(a)(1)(B)).

2. Prejudgment Interest

A successful claimant is entitled to prejudgment interest. Vega, supra. When awarding prejudgment interest in an action brought under ERISA, it is appropriate for the District Court to look to state law for guidance in determining the rate of interest. Hansen v. Continental Insurance Co., 940 F.2d 971, 984 (5th Cir. 1991). According to the Court in Hansen, the district court has the option of using the Texas statutory rate for contract actions, V.A.T.S. Finance Code, ‘ 302.002 (6% per annum compounding from date payment due on stream of benefits analysis) or the Texas statutory rate for other actions, V.A.T.S. Finance Code, ‘ 304.103 (7.75% simple interest on entire judgment). After Hansen was decided, the Texas Supreme Court held that all prejudgment interest calculations, including those for contract actions, should be decided in accordance with the prejudgment interest statute. See Johnson & Higgins of Texas, Inc. v. Kenneco Energy Inc. 962 S.W. 2d 507, 532 (Tex. 1998).

3. Discretionary Attorney’s Fees

ERISA, in 29 U.S.C. ‘ 1132 (g)(1), provides for an award of reasonable attorneys fees and costs to either party at the Court=s discretion. The 5th Circuit in Vega v. Nat=l Life Ins. Servs., Inc., 188 F. 3d 287, 302 (5th Cir. 1999), held that the Court should award attorneys fees upon a finding that an ERISA administrator abused it=s discretion.

Attorney fees awards in ERISA cases are typically made using the Lodestar approach. In the Fifth Circuit, a claimant must establish the reasonableness of the fees sought based on the factors set out in Johnson v. Georgia Highway Exp., Inc. 488 F.2d 714 (5th Cir. 1974) (the Johnson factors). These include: (1) the time and labor required, (2) the novelty and difficulty of the questions, (3) the skills necessary to perform the legal services properly, (4) the preclusion of other employment by the attorney due to the acceptance of the case, (5) the customary fee, (6) whether the fee is fixed or contingent, (7) time limitations imposed by the client or other circumstances, (8) the amount of money involved and the results obtained, (9) the experience, reputation and ability of the attorney, (10) the undesirability of the case, (11) the nature and length of the professional relationship with the client and (12) awards in similar cases.

a. pre-lawsuit – in the Fifth Circuit there are no attorney=s fees allowed for attorney work in the claim process.

b. lawsuit – attorney=s fees and cost of the action are discretionary with the district court.

c. what are reasonable and necessary attorney’s fees.

- discretion of the court 29 U.S.C. ‘ 1132(g)(1); and

- five factors in the Fifth Circuit:

- degree of opposing party’s culpability,

- ability of opposing party to satisfy award of attorney’s fees,

- deterrent effect of award on other persons,

- whether party requesting fees sought to benefit all participants in the plan or to resolve a significant legal question regarding ERISA, and

- relative merits of the party’s position.

CONCLUSION

ERISA plans typically confer a level of deference on a claim decider, often an insurance company, which is not seen in most other insurance claims. Traditional protections, such as the duty of good faith and fair dealing, the protections enumerated in the Texas Insurance Code, and even the right to trial by jury for an aggrieved claimant are notably absent. This does not mean that there are no protections, however.

The ERISA statute provides a clear outline of rights available under law. Federal regulations provide a comprehensive framework for enforcing those rights, detailing the steps necessary to provide a claimant a fair determination of his claim.

Finally, an increasing awareness of the challenges administrators face when they determine claims while burdened by an inherent conflict of interest is leading the federal courts to more closely scrutinize those instances where it appears the administrator was influenced more by its bottom line, than by its duty to fairly determine a claim.

While these protections are different than those that might be available in traditional insurance matters, they can be powerful. When used with skill, they help level the playing field for those with claims against health, disability, and life insurers governed by ERISA.

<- Back to Part 1

<- Back to Part 2

The team of disability lawyers at Bemis, Roach & Reed knows how crucial disability benefits can be for maintaining financial stability. Our attorneys are assisting clients with their disability cases in cities all across Texas, including Austin, Houston, Dallas, Fort Worth, Galveston, and Corpus Christi. If you are seeking disability benefits because of a sleep apnea diagnosis, contact our attorneys today at no cost to you. Contact us today for a free consultation.

Call 512-454-4000 and get help NOW.

Try these links for further reading on this subject:

Author: Attorney Greg Reed has been practicing law for 29 years. He is Superlawyers rated by Thomson Reuters and is Top AV Preeminent® and Client Champion Gold rated by Martindale Hubbell. Through his extensive litigation Mr. Reed obtained board certification from the Texas Board of Legal Specialization. Greg is admitted to practice in the United States District Court - all Texas Districts and the United States Court of Appeals-Fifth Circuit. Mr. Reed is a member of the Travis County Bar Association, Texas Trial Lawyers Association, past Director of the Capital Area Trial Lawyers Association, and an Associate member of the American Board of Trial Advocates. Mr. Reed and all the members of Bemis, Roach & Reed have been active participants in the Travis County Lawyer referral service.

Your Free Initial Consultation

Call now:

At Bemis, Roach and Reed, if we can't help you, we will try to find the right attorneys for you.

We offer each of our prospective clients a free no obligation one hour phone or office consultation to see if we can help you and if you are comfortable with us. We know how difficult a time like this can be and how hard the decisions are. If we can be of assistance to you and help you find a solution to your issue we will even if that means referring you to another attorney.

Let's get you Started:

If you could provide us with some basic information about your claim we will get right back with you with a free case evaluation and schedule your Free Consultation Today.